WoodworkingEarth

Woodworking Finishing Techniques

By Kristin Arzt

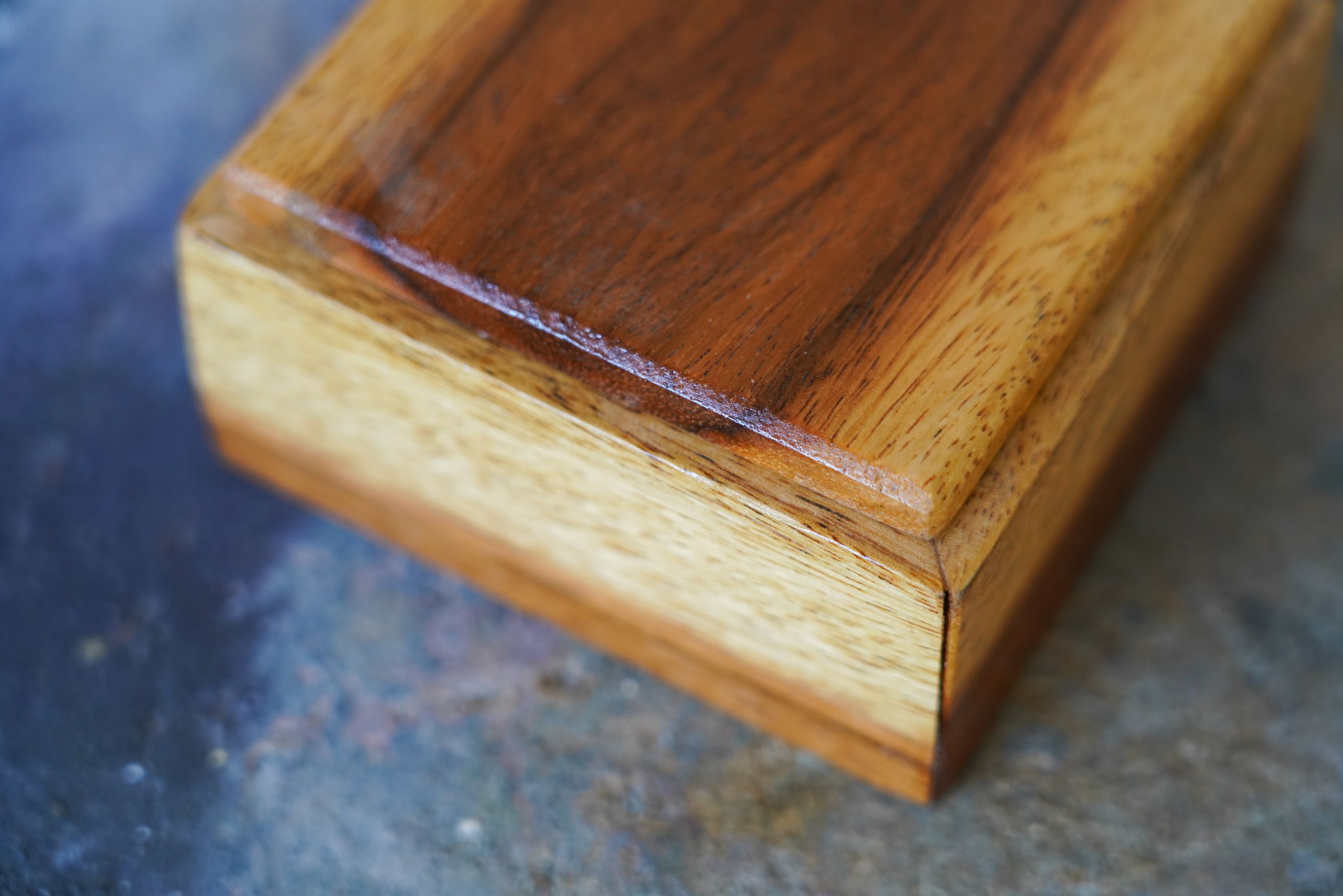

Most types of wood will easily pick up scratches, dings, and dirt, and oil and liquids will always leave marks. Wood can also shrink or expand in response to the moisture in the air. Finishes, to varying degrees, protect the wood from all of the above, either with a protective layer over the top or by penetrating the surface and hardening there. Additionally, most finishes will accentuate the grain, and when a number of coats are built up make it really shine.

Penetrating finishes are oil-based and absorbed by the wood. They are easier to apply than surface finishes and give the wood a more natural look.

Surface finishes dry on top of the wood to create a protective coating. Paint, polyurethane, and shellac are all examples of surface finishes. They offer durable protection and are a good choice for wood pieces that receive a lot of wear, like exterior furniture or a frequently used countertop.

Pro tip: Because finishes seal the wood, be sure to always apply the finish to the hidden parts also, to ensure that the wood reacts to changes in humidity uniformly. A coat or two is enough in the hidden areas.

Application Methods: Brushed, Sprayed, Wiped

The majority of finishes are designed to be applied by brush, which requires care to get even results and avoid sagging or drip marks. Brushed finishes tend to go on thicker than wiped or sprayed, usually requiring fewer coats. When brushing, try to keep the parts being worked on horizontally and take care at the edges to keep drips from running down.

Sprayed-on finishes allow fast, thin coats that can be built up, but good results require a proper spray gun setup, along with a spray booth of some kind, and hence are generally only used commercially. Many finishes can be thinned for spraying in such systems, but some finishes are available in aerosol cans, and while they have some of the advantages of spraying, they’re hard to achieve the same results with and have their own learning curve.

Wipe-on oil finishes provide an easy method to get a good result. The finish is worked into the wood using a soft cloth, allowed to sit a little while, then wiped off. These coats go on thinner than with a brush, requiring more of them, but dry a bit faster. They are mostly free of drips and sags and tend not to capture as much dust while drying. Some brushed finishes can be adapted for wiping.

Stains & Dyes vs. Finishes

Stains & dyes color the wood by adding ground pigment or dye to the surface, generally to mimic various wood species. Dyes are a bit less common but offer a wider palette of colors. The pigments in stains are generally light-fast, but most dyes will fade over time if exposed to sunlight. Stains tend to obscure the character of attractive wood, but can be a useful way to tint inexpensive varieties. Neither does much to protect and should have coats of finish applied over them.

Gloss/Semi-Gloss/Satin/Flat

Most finishes are Glossy by default. Non-Glossy finishes contain particles to break up the light. Glossy finishes can be more difficult to apply without streaks. Be sure and continue to stir non-glossy finishes while using them to keep the particles uniformly mixed in. One can also “rub out” a dried Gloss finish with super-fine steel wool to achieve many variations between glossy and flat.

Types of Finishes

Food-Safe Finishes

While many finishes are functionally non-toxic once they’ve completely dried (Shellac is still used on candy!), the majority include various solvents to aid in applying them. For explicitly safe finishing one can turn to mineral oil or beeswax.

Bowls, cutting boards, etc. are usually finished with mineral oil, and a number of commercial finishes for the purpose exist, but they’re generally the same as mineral oil available at the drugstore. Use a rag to put on as much as the wood will absorb, and keep adding more when it looks dry. Beeswax can be buffed to a nice shine and is sometimes applied over oil. Neither adds any hardness, but they do seal the wood, and it’s easy to apply more at any time.

Wax

Furniture wax, or “paste wax”, was traditionally from beeswax, though most products currently use the more durable plant-based carnauba wax. Paste wax doesn’t provide much protection but is often used as a polishing layer over many other types of finish. The wax comes mixed with thinners of various kinds to form a paste that can be easily smeared onto the surface, allowed to dry, then buffed to a shine with a soft cloth. Using it with super-fine steel wool is a way to polish an uneven finish, but should be done after the underlying product has fully cured.

Paint

Milk paint, enamels, oil-based, artist acrylics: just about any paint is acceptable. Dry wood generally takes paint quite well. In most cases, paint-grade projects are done with cheaper species. Priming is sometimes useful, depending on the quality of the finish desired. Water-based paints will raise the grain some, so for very smooth results, sand the first coat before adding another. Many paints are thick enough to require only one coat.

Varnish

“Varnish” is an old, somewhat generic term for tough clear topcoat products. Traditionally they were made by dissolving natural resins (sap, amber, cellulose, etc.) in heated oils. Today they’re made in all sorts of ways, both for interior and exterior. Most are brushed on and take some care to get good results, though they can often be adapted for wiping. Products sold as “varnish” tend to produce a rather heavy result for fine furniture, though some woodworkers make mixtures involving things like “spar varnish” as a component in order to add toughness.