His work recently made waves when an impassioned British public petitioned to have his Endangered Species Sculptures salvaged from near-certain destruction; now, the sculptures are headed toward the Titanic project in Belfast. He has spent the past decade cementing his legacy at The Crucible. For a deeper look, staff writer, Sarah Dabby interviews him about his travels, his legacy, and his upcoming five-week summer stone carving course.

Sarah Dabby: Tell us how you got into stone carving.

Barry Baldwin: I went to art school when I was 16. I started off as a painter, but I finally did sculpture. I had an affinity for carving stone. I actually got a job from art school, which is really unusual. So from art school, I became a stone-carving assistant for a couple of very famous sculptors back in England, and that was the beginning of my career. I got my own jobs after that – when I was in my early 20s, really. From there on in, I ran my own stone yard and did various jobs. You can find me on the Internet – I’m quite famous, actually.

SD: You mentioned that stone carving has taken you all over the world. Can you elaborate on that?

BB: Well, you know, mankind has a habit of blowing places up, places like Belfast and Beirut and places like that. As stone carvers, we’re part of the emergency services, really. When the fire brigade and ambulance people have taken over, we normally go in there and sort out all the buildings and carvings that have been ruined. So yeah, I did my fair share of replacement of carvings throughout the world. That’s part of the role of someone who does stone work, and that’s been part of my job.

SD: What brought you to the Bay Area?

BB: I wanted a break, actually, because I’d had enough. I was almost worked to death, really, in Europe, and I just wanted to get away. I had been to the Bay Area – I had been offered a job in America about a decade earlier, and I didn’t take the job. But I decided just to come and take a chance, really. Take a chance at just having a more peaceful life. And that’s certainly what I got.

SD: So you discovered The Crucible shortly after you arrived, then?

BB: I actually discovered The Crucible while I was in Europe. I wrote to Michael Sturtz, actually, and he wrote back and invited me over, he invited me to come teach here. That was over a decade ago. In fact, I don’t think there was any carving here at all, until I took it over. And now I’d like to leave it to one of my students, really – I’d like to leave a legacy of teaching stone carving to one of my students at The Crucible.

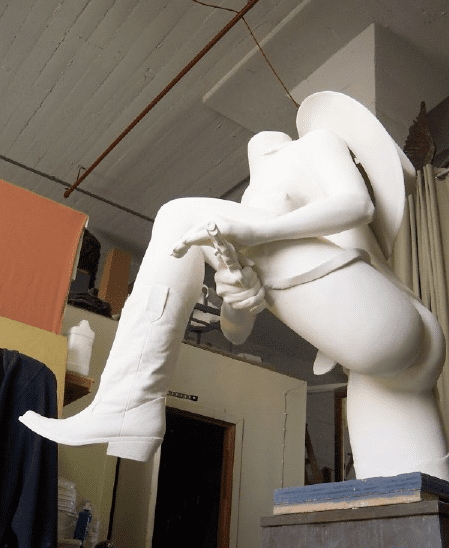

Hormona Lisa by Barry Baldwin

SD: What kind of legacy have you tried to build here at The Crucible?

BB: My legacy is actually born from being a boy, really – a boyhood apprenticeship in stone. Living in a stone area, quarrying, all the processes to do with stone, and handing them on, really, has been my forte – so I’m proud of the fact that I’ve done that, and that there are students here that are a testament to that. In my opinion, the legacy is the people that are left behind – the people who know about stone carving, who can hand off the knowledge, my students; the people who pass through The Crucible.

SD: You’re offering a course this summer.

BB: The course is good, really, because it’s over a five-week period. In the ordinary terms in autumn and winter term, the courses are over 10 weeks, so it’s once a week, and I think that’s spread out a little too far. But the summer courses are over five weeks, so it’s twice a week, so you never get a chance to get bored, so it’s pretty intensive. And you learn the basics of stone – everything about stone.

SD: What do the students walk away with?

BB: They walk away with a lot more than a product. They walk away with this kind of confidence. Quite a few people who contemplate stone, they think ‘oh it’s so technically difficult,’ and a lot of people shy away from the technique. But after doing my course, it’s refreshing to see how people regard it in a different light. They’re far more confident, they can’t wait to come to my studio after the course. I have a lot of students who come to my studio, and have been for 2-3 years, as a continuation as what began at The Crucible.

SD: You’re going back to Europe soon. What are some of the projects you’re tackling there?

SD: You’re going back to Europe soon. What are some of the projects you’re tackling there?

BB: One of my sculptures has been saved in London from the garbage bin, it’s a big piece of sculpture, weighs 18 tons, and it’s very popular. It was actually saved by a campaign – not started by me, but I became part of the campaign. It was an 8-month campaign to save the sculpture, so they’ve saved it, and now it’s on its way to Belfast, to the Titanic project. So that’s my next project – I probably have to go there and do a few repairs on the piece.

SD: Let’s play high-low. Can you tell me about the highest moment and lowest moment of your professional career?

BB: Highest moment? Highest moment…probably being awarded a big award for my work on Trafalgar Square and the carvings there, by the Stone Federation of Great Britain, so that was probably the highest moment…we had a big celebration, you know, and a lot of accolades.

Lowest moment? I don’t know whether there’s been a really low moment. I suppose selling my blood in Athens, and living on a hotel roof for a year of my life – but actually, having said that, I did study a lot of Greek sculpture at the time, the Acropolis and stuff, and it was my choice not to make a living, but to just sell my blood. You know, it’s one of those crazy times, really. I mean, what can you say in a few minutes? I’ve got a lot of low moments, and a lot of high moments, as we all have really.

On right: Carved doorway in the south-east corner of Trafalgar Square, London, England.